PR Yu is the founder and managing partner of Yu Galaxy, a Silicon Valley–based solo-GP venture firm, investing from seed to Series B in healthcare, AI, defense, automation and more. In October 2025, Yu Galaxy announced the close of Fund III at $90 million alongside an SPV, bringing total assets under management to $500 million.

Yu earned a B.S. from Peking University and a Ph.D. in physical chemistry on a full scholarship from the University of Colorado Boulder. Before venture capital, he was a serial entrepreneur, clean-energy scientist, inventor, and executive, including roles at Innovalight (acquired by DuPont) and as founder-CEO of Optony. He has invested in more than 100 startups.

In this conversation with Scott Douglas Jacobsen, Yu argues that the solo-GP model reduces diffusion of accountability while improving decision consistency and speed. In early-stage venture investing, where incomplete information is unavoidable, Yu believes decision quality depends less on consensus and more on conviction, technical fluency, and accountability. A values-based investor, he defines impact as the number of lives positively affected, linking ethical clarity directly to market viability and long-term returns.

Jacobsen: You run a solo-GP model at institutional scale. What does that structure permit philosophically and operationally?

Yu: At a philosophical level, a solo-GP investment model eliminates the diffusion of responsibility and accountability. Operationally, it enables high efficiency and consistency.

I don’t have a decision-making committee. And the core issue here is decision-making itself. The quality and efficiency of decisions are fundamental in venture capital. As a solo GP, I carry 100 percent of the responsibility and accountability. That leads to consistency and speed—very different from the traditional model where multiple partners must reach agreement on a deal.

Decision-making and interaction consistency with founders, LPs, and other stakeholders are strong across the board because it’s just me. I can deploy both capital and service with velocity.

Efficiency is critical. When I have conviction, we can move in hours or days. In traditional venture models, people move through layers of process, structure, and voting thresholds. That can take months. Even when a partner wants to move forward, the final decision may be delayed indefinitely. For founders, that uncertainty can be brutal.

Jacobsen: Speed clearly matters. But what about situations where slowing down improves decision quality?

Yu: That’s a very good question. If we had ten days, we could unpack decision-making in detail—intuition versus analysis and how they converge, etc. But let me frame it more simply.

In venture capital, decisions are made with incomplete information. That’s unavoidable. You don’t know how the market will evolve. Sometimes you don’t know whether the technology will ultimately work. Early-stage investing is defined by uncertainty.

So the question becomes: when information is incomplete, do three people necessarily make a better decision than one? Philosophically and analytically, the answer is not necessarily.

What matters is the depth of understanding under uncertainty. Once you add multiple people, their experience and decision frameworks diverge. And if the structure requires consensus, everyone must feel comfortable. But comfort usually means reduced uncertainty—and that’s fundamentally misaligned with what good venture capital is supposed to do.

Good venture capital requires seeing opportunity where risk appears high, having conviction, committing early, and doing the work to make it succeed. If a billion people all agree on a deal, by definition it’s not a good venture deal.

From the entrepreneur’s perspective, speed matters even more. Startups need to move quickly. If decisions on the venture side take months, opportunities might be lost and nobody wins.

Jacobsen: How do you determine when to rely on others’ judgment, especially when expertise differs?

Yu: I have asked for input from domain experts, however I have never outsourced an investment decision. If I don’t understand a deal, I don’t invest. I can give you many examples where I was the only investor. I cannot give you a single example where other well-known VCs invested, I didn’t understand the deal, and I still invested. That has never happened.

Conviction is non-negotiable. I have to know the deal. I have to believe in it fully.

Jacobsen: You’ve said impact and profit are two sides of the same coin. How do you define impact in a way that holds up against competitive markets?

Yu: Impact is defined in many ways. At Yu Galaxy, we keep it simple: impact is the number of people whose lives we positively affect. That’s it.

It’s a humanistic definition. With every company we invest in, we ask how many lives are positively affected, directly or indirectly. In healthcare, this is especially clear. Several of our portfolio companies are actively saving lives around the world today.

If a company cannot compete on price or survive market dynamics, it cannot make a large impact. The market won’t allow it. That’s why impact and profit are inseparable.

Many of our companies are category-defining—first of their kind. When you are truly first, there is often no close second competitor. That’s when you see very high margins. Pricing is based on value, not cost.

When a company is genuinely N-of-1, competition matters less than whether the value delivered justifies the price. That’s how you build both impact and strong economics.

Jacobsen: Where do you see true N-of-1 categories emerging, and how does your values-based model enable them?

Yu: I’ll use our portfolio company Capstan as an example. Earlier this year, they became the first company in the world to deploy a robotic surgical system capable of transforming heart surgery. They are already saving lives across multiple countries.

There is no close competition. Today, severe heart disease often requires opening the chest and stopping the heart—an extremely traumatic procedure many patients cannot survive. Capstan’s system enables surgery without opening the chest or stopping the heart.

Almost one million Americans die each year from heart disease because there has been no viable alternative. Now there is.

I invested early because my values—passion, service, and growth—aligned perfectly with their mission. At the end of the day, I care about whether it works and whether patients can afford it. With Capstan, the answer is yes. High margins and real impact can coexist.

Jacobsen: What are your non-negotiable diligence standards?

Yu: We underwrite people, not projects.

Of course we do technical diligence. But the most important questions are about the founders: their passion, motivation, experience, and vision. What are they willing to dedicate the next ten or twenty years of their lives to?

If you have the right people, they can navigate uncertainty. It’s like sailing across the ocean. You don’t need mile-by-mile forecasts. You need a capable captain. That’s non-negotiable.

Jacobsen: How do you balance speed with restraint?

Yu: I think of us as first responders.

We spend most of our time learning, reflecting, analyzing—preparing for moments when speed truly matters. First responders aren’t reckless. They act quickly and precisely when needed.

Speed is our superpower in decision-making, not in operations. I was an entrepreneur for ten years before becoming a VC. I became a VC because I wanted to support founders the way I once needed support—where speed and service both mattered.

From the outside, venture capital can look easy. But most of the work is invisible. I’m working all the time mentally—thinking, learning, evaluating. We don’t make many large decisions each year, but when we do, they are fast, high-conviction, and carefully prepared.

Preparation is the work. Action is just the moment.

Jacobsen: You invest across a wide range of areas—AI, automation, defense, and healthcare. Where are the ethical red lines for you?

Yu: For us, ethics are not optional. They’re foundational. I’m not interested in building wealth from products or systems that undermine people’s health, mental well-being, or long-term stability—even when the harm may not be immediately visible.

There are many businesses that are financially successful precisely because they exploit human vulnerability, attention, or addiction. That kind of success doesn’t align with our values. Even if those models are legal or widely accepted, they’re not something I want to be part of.

Jacobsen: At Yu Galaxy, you have very specific core values, and certain types of businesses clearly violate those values.

Yu: Yes. Our fundamental value comes back to how we define impact. For us, impact is measured by how many lives we positively affect—and in some cases, how many lives we help save.

Anything that predictably harms people, especially children or vulnerable populations, is the opposite of what we’re trying to do. It detracts from human potential rather than expanding it.

Jacobsen: Can you give an example of how this shows up in practice—particularly in relation to women, minorities, or children?

Yu: We’re very clear that we won’t harm anyone—women, minorities, or children. That clarity shapes what we choose not to invest in, but also what we actively support.

One reason we’re so excited about companies like Leo Cancer Care is that their work directly improves patient outcomes and quality of life. Radiotherapy cures more than half of cancer patients across cancer types, and precision advances are especially meaningful for pediatric care. That’s a very tangible form of impact. Children’s experiences and outcomes are being significantly improved.

So while we’re careful about where we draw our boundaries, we’re even more intentional about where we direct our energy—toward technologies that heal, protect, and strengthen people.

Jacobsen: In your ideal world, if industries built around harm or addiction weren’t dominant, what would replace them? What fills that void?

Yu: I’ll answer that with one word: nature.

Especially for children, but really for everyone, we need more connection to the natural world—not less. Let people go outside. Let them move, explore, grow food, touch soil, see how things are planted and harvested. That kind of engagement is deeply satisfying in a way screens and artificial stimulation can’t replicate.

A big reason so many people struggle physically and mentally today is that we’ve become increasingly disconnected from nature. Reconnecting with it is profoundly healing.

There are already encouraging examples—urban gardening programs in cities like Detroit and Chicago that help children reconnect with food, land, and community. That’s the kind of work we’re interested in amplifying.

When I talk about nature, I don’t mean rejecting technology or modern life. I mean remembering that we are part of a larger system. We are healthier—individually and collectively—when our solutions respect that interconnectedness rather than ignoring it.

Jacobsen: This brings to mind the quote—often attributed to Whitehead—that all of Western philosophy is a footnote to Plato. The idea being that much of human thought, even today, is grounded in the thinking of those long deceased. Is there a philosophical movement or stance that most closely aligns with what you view as philosophically appropriate and ethically sound today?

Yu: A few strands come to mind, though I’ve never approached this question in a purely academic way. My training is as a scientist—I have a Ph.D. in physical chemistry—so when I think about big questions, I instinctively treat them like a research problem: observe, collect evidence, analyze patterns, and only then draw conclusions.

One perspective comes directly from science itself. If you look at the human body, every atom in it was created billions of years ago. If you accept the Big Bang theory, those atoms were formed at the same moment as everything else in the universe. There isn’t a single atom in our bodies that is truly “new.”

We constantly exchange atoms with nature—through breathing, eating, living—and eventually we return all of them. From that standpoint alone, it’s very clear: we are not separate from nature. We are part of it.

Another influence comes from Chinese philosophy, particularly Daoism, which I grew up with.

Jacobsen: I read the Dao De Jing maybe a dozen times as a teenager at my friend’s dad’s house.

Yu: That’s my favorite text. I used to be able to recite most of it. It speaks directly to this idea that because we are part of nature, we should learn from nature. In Daoism, the highest form of a human being is not someone who dominates or extracts, but someone who cultivates themselves in harmony with natural principles—or at least walks in that direction.

That philosophy shaped me early on.

There’s also a more experiential layer to this, one rooted in observation rather than theory. Because we are part of nature, we naturally resonate with it. When we see a flower bloom, we don’t need an explanation to feel something. When we watch a bird fly, or look at a blue sky with white clouds, it gives us a sense of life and positive energy. This response is instinctive.

Many people try to analyze why this happens, but we don’t actually need to know why for it to be true.

I like gardening. Growing up, our family planted much of the food we ate. I grew up in a small village in China, and I made my own toys and invented games to play. By today’s standards, we didn’t have much money—but I was very happy.

That experience stayed with me.

Today, I still plant fruit trees in my backyard. Gardening remains one of my favorite activities. Even something like golf, for me, is really about walking through nature.

When I talk about “going back to nature,” there are philosophical ideas behind it, but it’s also deeply personal. From lived experience, I’ve seen how grounding it is.

What’s striking to me is how universal this is. Regardless of culture, religion, age, or background, people respond positively to nature. I’ve never met a group of people—no matter how different their beliefs—who don’t appreciate a beautiful landscape, flowers, or open sky.

That’s a simple fact. And sometimes we need to allow ourselves to be surprised by simple facts.

Jacobsen: That is a paraphrase of Chomsky, probably. As he put it, once you allow yourself to be puzzled, you begin to make discoveries. Being puzzled by nature is the basis for discovery.

Yu: Exactly. Curiosity begins with not knowing. It begins with allowing yourself to be puzzled. And that stance—toward nature, toward life, toward other people—is not just the foundation of science. It’s a way of living.

Jacobsen: Many people tend to have a North Star when they begin pursuing something. In your ethical investment history, was there a North Star—something that guided you as you developed your own path?

Yu: I don’t think it’s one thing. It’s more like a stream of things that come together over time. I remember one of your quotes—something like, “Life is an expression of your thoughts.”

Jacobsen: I stole that. That’s Marcus Aurelius.

Yu: I like him too.

I feel extremely lucky to have had the life I’ve had. I feel genuinely grateful. I shared earlier that I had a happy childhood. I went to excellent schools, learned from great professors, made lifelong friends. I’ve had an exciting career, and even now I get to learn from creative, thoughtful people every day.

I feel fortunate—and because of that, I want more people to have access to the kinds of experiences that shaped my life.

That’s where what I call the “three Es” comes from. You could say that’s my North Star.

The three Es are education, entrepreneurship, and experience.

Education is foundational. Other than nature, it may be the most powerful force in a person’s life. I benefited enormously from access to education, and I want more people to have access to knowledge and information.

Entrepreneurship is a mindset. It’s the belief that there is always a better way to do something. Everyone is an entrepreneur in some sense—we create, we adapt, we solve problems. It’s easy to forget that, but it’s a simple and important truth.

And experience matters deeply. Real understanding comes not just from reading or learning, but from doing, from trying, from living through challenges, discovery and fun.

Jacobsen: What about philanthropy focused on educational programs for entrepreneurs and founders?

Yu: I don’t separate investment from philanthropy completely, as both are intended to do good, sometimes even in similar ways.

The first of my three Es is education, and that principle shows up everywhere in my life. In my investments, sometimes I think of a startup as a group learning journey, a form of education. I support companies that help people access information, tools, and opportunities more easily. On the philanthropy side, I significantly support many educational programs ranging from K–12 schools to universities, and I plan to do much more.

Even before I became a venture capitalist, I saw things this way: I don’t need much money to be happy. I can be happy with one dollar a day. I lived on less than that as a child, and I was happy.

As a venture capitalist, I’m fortunate that I may accumulate more wealth over time. The real question then becomes: What is that wealth for?

For me, a significant portion will go toward philanthropy—especially in areas aligned with the three Es: education, entrepreneurship, and experience. Those are the forces that shaped my life, and I want them to shape the lives of many others.

Jacobsen: What do you want to be on your gravestone?

Yu: I haven’t really thought about that, but let me try.

We’re talking about legacy. I think I would want to be remembered as someone who did what was right—even when it was harder, and even when it would have been easier to do what was wrong.

At the same time, I don’t know if I should be the one to write what goes on my tombstone. I don’t want to be grandiose.

My first reaction to your question, without much thought, is very simple: life is beautiful.

I would keep it simple, because life is a beautiful thing.

We are fortunate to have the human form—to have a human life. I don’t come from a religious background, so I approach this from scientific reasoning and from theories I’m familiar with. From a scientific perspective, it is extraordinarily rare for us to exist in human form at all. It’s a very low-probability event.

The probability of us having this conversation—close to Christmas in 2025—is extremely low. These are rare events layered on top of one another.

I hope more people don’t lose appreciation for that.

I know life can be very hard. You’ve been to Ukraine. I feel deeply for people living in war zones. People die. In those situations, life can feel miserable. People with devastating illnesses suffer.

Even so, I hope that most people—whatever happens to them—don’t lose sight of how fortunate we are to have this human life. Statistically, it is incredibly rare.

Life is beautiful. Don’t lose sight of that.

Even when we are suffering, there is still great beauty in life.

So perhaps “life is beautiful” could simply be on my tombstone, and people can interpret it for themselves. I hope that when they see it, they think about the beauty in their own lives—and maybe spread that beauty.

Even a simple act—looking at the sky, or a beautiful cloud—reminds us that appreciating beauty costs nothing. We lose nothing by sharing beauty, and we all gain something by seeing it and passing it on.

I know this answer is a bit off-topic for venture capital, but it was my first, honest reaction to your question.

Jacobsen: You mentioned earlier a formula you use to redefine venture capital as a force multiplier for human progress—how many lives are saved, how many problems are solved. For those outcomes, what are the leading indicators before the headline milestones?

Yu: When we invest in startups, I don’t view them very differently from other life forms.

A startup grows from an idea into a small team, then into something larger, and eventually into something that can make a significant impact. In that sense, it’s a life form—much like a tree growing from a seed. As it grows, it provides more shade, more leaves, more fruit.

When it comes to early indicators for startups, I look at two things.

The first is consistency. The fact that I invested means the vision, the people, and the dream convinced me. What I want to see is consistency—actions matching the story. Do people do what they say they will do? If that consistency is there, that’s the first box to check.

The second indicator, even before any headline milestones, is direction.

Are we directionally on track? Are we building not just bigger teams, but better teams? Are we solving technical challenges one by one?

I use the word directionally very intentionally. At this stage, there are no headline milestones yet. Building a startup involves significant uncertainty. Direction matters.

Sometimes progress is faster. Sometimes it’s slower. But as long as the direction is right, you know meaningful impact is coming.

If the direction is wrong, moving faster only makes things worse.

Jacobsen: What do you consider your most positive impact investment so far in your career?

Yu: There are a few, and many are still early. But I feel very excited about them.

I can name two for now, though they’re not the only ones. Leo Cancer Care is one. Capstan is the other. I mentioned both earlier.

I highlight these two because they are already achieving results. They are already saving lives as we speak. This is no longer a theory or an aspiration—it’s reality.

They also happen to be addressing the number one and number two causes of death in our society.

Because we care about positively impacting people’s lives and saving lives, I’ll be very happy as these companies mature and save more and more lives. Who knows—perhaps someday, because of their existence and impact, and the small role we played, heart disease and cancer could be removed from the most lethal causes of death.

Jacobsen: Do you have any favorite aphorisms or quotes to close off the interview?

Yu: I don’t have a single favorite. There are many good ones.

I might come back to you on this later. The reason is that I’m still learning. I’m still improving. I try to keep an open mind.

I benefit from many different ideas, and I haven’t settled on one quote that guides my entire life. I’m not there yet.

Scott Douglas Jacobsen is the publisher of In-Sight Publishing (ISBN: 978-1-0692343) and Editor-in-Chief of In-Sight: Interviews (ISSN: 2369-6885). He writes for The Good Men Project,International Policy Digest (ISSN: 2332–9416), The Humanist (Print: ISSN 0018-7399; Online: ISSN 2163-3576), Basic Income Earth Network (UK Registered Charity 1177066), A Further Inquiry, and other media. He is a member in good standing of numerous media organizations.

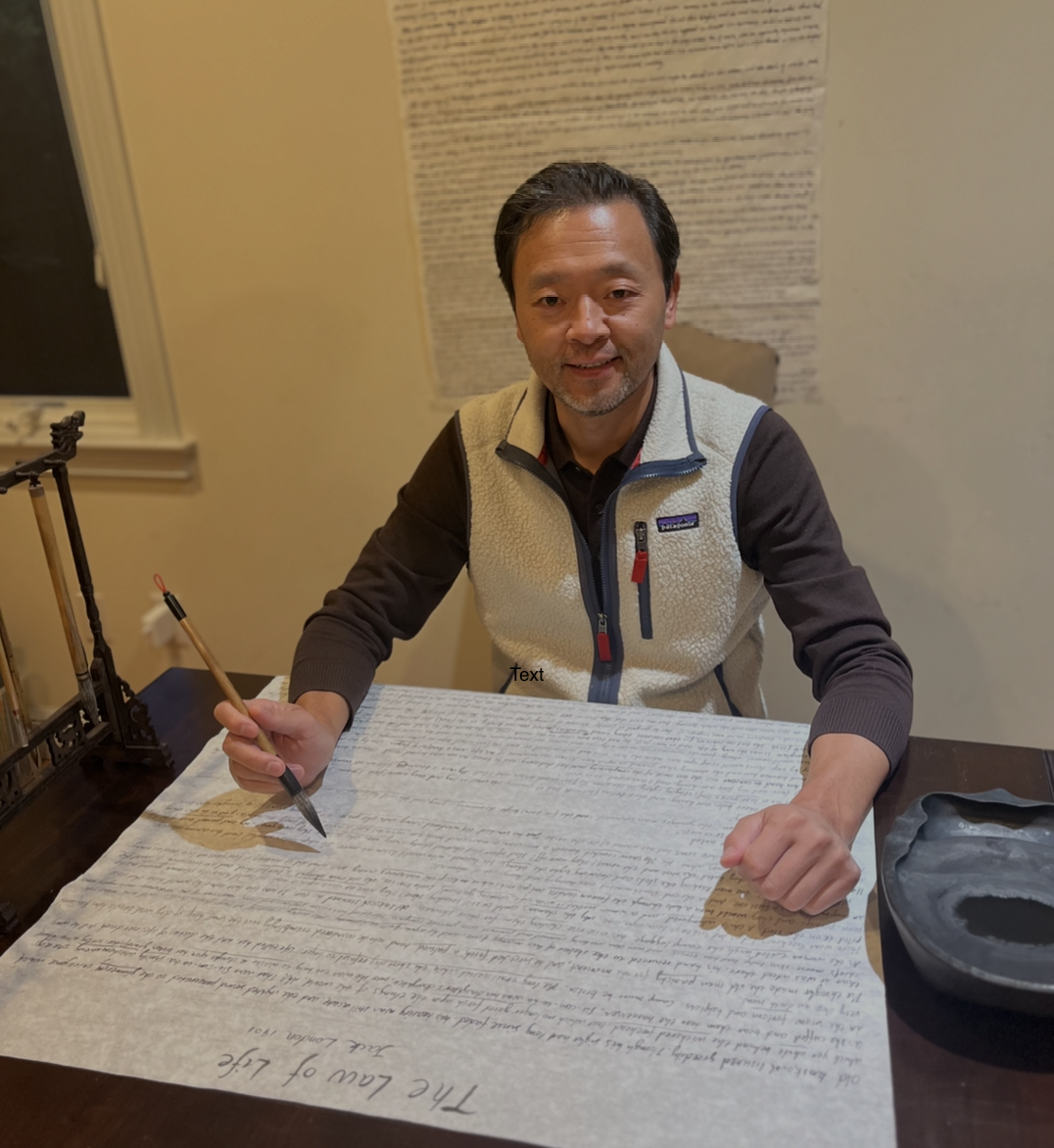

Image Credit: PR Yu.